Nonprofits are under-theorized

The low church politics of America

Canadians are notorious America watchers. Growing up, I was no different.

The trigger for me was 9/11. After the second plane struck during my 4th grade homeroom class, our teacher informed us something terrible had happened but that we had to wait until we got home to learn more from our parents. I resented being denied the full story, so from then on I hid a portable FM radio in my desk to always have real-time access to the news. To my young mind it felt like history had begun despite my ignorance that it had ever ended.

Canada remains blessed as one of the few countries where the End of History thesis lives on. The stability of our consensus-driven politics and the ministerial strength of our executive institutions creates natural defense mechanisms against populisms of every stripe. We have our share of scandals, but they are comically trivial compared to what goes on in the States. While Canada plods along offering internal improvements and pragmatic accommodations at the first hint of instability, our neighbor to the South seems to perpetually teeter on a knife edge between reaction and revolution.

Boring politics are a feature, not a bug. Yet as I watched the War in Iraq unfold against the backdrop of Code Pink protests and schismatic blog debates, my fascination with American politics and policy only grew. I selfishly wished I could live in such interesting times, and perhaps do my small part to make them boring.

Think tank theology

Studying the output of American think tanks became an obsession. For better or worse (though mostly for the better), think tanks are a foreign commodity in Canada. Sure, we have organizations like the Fraser Institute and C.D. Howe, but they fill a narrow niche. Bigger picture, most Canadian think tanks are little more than PO boxes with a landing page.

Canada’s austere job market for independent policy wonks is downstream of our strong party system. Governing parties don’t need to outsource their policy development, and when they do, ideas can be supplied by ad hoc committees, commissions, and consultants that evaporate into the ether when their work is done. The parties themselves are highly member-driven. Some of my earliest memories were from the stuffy basement of our local Liberal Party HQ where my parents volunteered. Though I barely understood what was going on, I relished the ritual of staying up past my bedtime to watch election results come in while old Anglican ladies manufactured triangular sandwiches.

American politics is a completely different beast. The framers of the US constitution had a hubristic aversion to partisan politics, and so designed a system of checks and balances that grants individual electeds enormous free agency. While transaction costs and Duverger's law made parties an inevitability, progressive anti-patronage reforms and the move to primary elections have long since eroded the social base for thick, membership-driven political parties and the efficient party machines they enabled.

Modern American think tanks, and the broader nonprofit advocacy world, emerged in their place. Ostensibly nonpartisan organizations such as the Center for American Progress and the American Enterprise Institute serve as holding tanks and convening spaces for Democratic and Republican functionaries while they’re in and out of power. Yet because the parties themselves contain internal factions, the establishment’s grip on power is provisional on the makeup of Congress and the disturbingly stochastic process behind party nominations. Given their tight staff budgets, lawmakers face a buyer's market of policy shops — an entire ideas industry — letting them outsource their legislative, communications, and networking strategies to whichever outfit overlaps with their political philosophy and electoral base: ultraconservatives can turn to the Heritage Foundation, trade unionists to the Economic Policy Institute, libertarians to the Kochs, and so on.

Other countries sometimes outsource to independent think tanks, too, but usually within the context of a formal parliamentary relationship. The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung in Germany, for instance, is an independent think tank that functions as the policy organ of the center-right Christian Democratic Union. Crucially, however, over 95% of its funding is public and they have no direct intraparty competitor.

Associations without members

In recent decades, ideological self-sorting and the consolidation of power under leadership has made Congress look and act more like a parliament, making Nancy Pelosi something like America’s prime minister. Yet without the complementary institutions that make parliaments work, it’s a tenuous equilibrium at best. The national parties, such that they still exist, are largely lifestyle brands attached to fundraising funnels. Unlike in actual parliamentary democracies, lawmakers have no direct obligation to vote with their party. Votes must instead be whipped through horse-trading and indirect sanctions, such as the denial of powerful committee assignments or the withdrawal of support on reelection campaigns.

The nonprofit advocacy world helps grease the wheel of party cohesion by mobilizing activists, lobbyists, pollsters and grassroots outreach whenever a big vote is afoot. While the number of such organizations may appear large and unruly, they typically derive core funding from a countable number of upstream foundations or philanthropists. Funders are drawn from a similar social class on both the left and right, and (within any given issue area) are close enough to Dunbar's number to enable interpersonal forms of coordination, i.e. the sorts of communicative action governed by trust, reputation, and conformity to shared norms. Yet given the insulation of funders and advocates from electoral imperatives, there is nothing to prevent them from spontaneously self-organizing around the sorts of self-defeating policy platforms that make David Shor cringe. On the contrary: without the moderating forces of intra-party bargaining within a consolidated party superstructure, ideological clichés become the only viable Shelling point for collective action.

Endemic political alienation is a predictable side-effect of America’s disintermediated power structure. The bulk of voters have weak identification with either major party, and, beyond casting the periodic plebiscite, are largely cut-out of democratic participation. While the old school patronage system had its ugly side, voters could at least expect that electing Joe Shmoe to Congress would get their community some money for a new post office or public park. This created programmatic linkages between democratic participation and policy outcomes, reinforcing faith in the system. I suspect the breakdown of those linkages, not just in the US but in countries around the world, created the tinder for populism and “The Revolt of the Public.” In the end, we didn’t so much dismantle the old patronage system as create an all new one, only through institutions that are far more performative than formative.

Steve Teles discussed these dynamics and more in a fascinating interview for Inside Philanthropy published earlier this year:

When we talk about how philanthropy can reduce polarization, don’t we also need to talk about ways it might change to stop driving this trend in the first place?

There’s no question that the growth of what Theda Skocpol has called “associations without members'' has grown in the last half-century, and mass membership organizations have shrunk. Before the 1960s, if you were an idealistic person who wanted to drive social change in some way, you really didn’t have much choice to either build a mass membership organization or work within one. But things really did change in the 1960s. Foundations like Ford and Rockefeller began to fund a huge network of organizations in law, civil rights, feminism, consumerism and the environment, a process I examined as the backdrop to my book “The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement.” Suddenly, if you were that idealistic person, you could skip over the step of building a mass movement and put out your shingle and start suing, lobbying and publishing. That model — a professionally staffed organization based in D.C., no members, funded primarily by foundations — came to be the dominant one on the center-left.

That helped generate some of the characteristic features of contemporary elite polarization. You've got what I’ve called “advocacy” rather than representation, in which groups claim to speak for constituencies that they don’t actually have any organic structures of accountability to. I think that has had some important impacts on both the left and right. On the left, it has simultaneously encouraged an embrace of positions on social issues that are not widely supported by the actual people being advocated for, but also a kind of piecemeal, bite-sized economic policy that flows out of the fact that they are not trying to organize mass constituencies. On the right, I think it encouraged an economic policy that was at odds with the actual preferences of conservative voters (but aligned with conservative donors, whose preferences ran strongly libertarian on economics) on things like entitlements and trade. One way to think about the politics of the last few decades is that we’ve had an ideological conflict on both social and economic issues as a consequence of the incentives of the organizations competing for attention; that has left broad swathes of what the public actually cares about relatively unorganized. So in that sense, I think it probably does make sense to say that philanthropy has had an impact on polarization in shaping what we think it is we are supposed to be fighting about.

All that being said, it is hard to imagine the polarizing role of nonprofits and big philanthropy fading anytime soon. Advocacy organizations on both sides are trapped in something of a prisoner’s dilemma: even if progressive and conservative funders recognize that they’re burning hoards of money while making our politics less functional, the incentive to defect is too great, as unilateral disarmament would simply cede territory to the other side. Instead, funders on the left and right have, if anything, a deep envy for each others’ total embrace of strategic rationality: progressives are perennially trying to create their own version of ALEC, while conservatives pine for the institutional money of progressives so they can stop being so reliant on decrepit billionaires.

Thus, despite a growing number of 501c(3)s, the number of "social welfare organizations and beneficent societies" fell 31 and 37 percent respectively between 2003 and 2013. The archetypical nonprofit is now no longer a church or soup kitchen but rather a vague educational organization. I don’t think this is what de Tocqueville had in mind.

Anti-social impact

Anecdotally, I suspect the spread of Potemkin civil society is the flip side of America’s overproduction of college-educated knowledge workers: if you’re unable to cut it at McKinsey, a nonprofit job is a good deal, providing lower but stable pay in exchange for a non-wage status benefit. On this point, I'll never forget the first time I met a Harvard student (they normally don’t visit rural Canada). It was in a big auditorium at my fraternity's international conference. The speaker, a successful alumnus, finished his remarks by asking us what we wanted to do with our careers. The one Harvard freshman in the audience stood up and declared, I shit you not, "I have a passion for nonprofit management." Everyone clapped. When even members of the British royal family start decamping for plump foundation jobs it's perhaps time we update our conceptions of nobility.

Of course, as a collective action problem, the advocacy arms race could be easily forestalled by amending nonprofit law or the US tax code. But who would fund that whitepaper? The endogeneity of US policymaking to organizations dependent on private philanthropy makes reforms aimed at reining in the sector nearly impossible to imagine. As a result, nonprofits and foundations remain deeply undertheorized compared to, say, corporate governance or public administration.

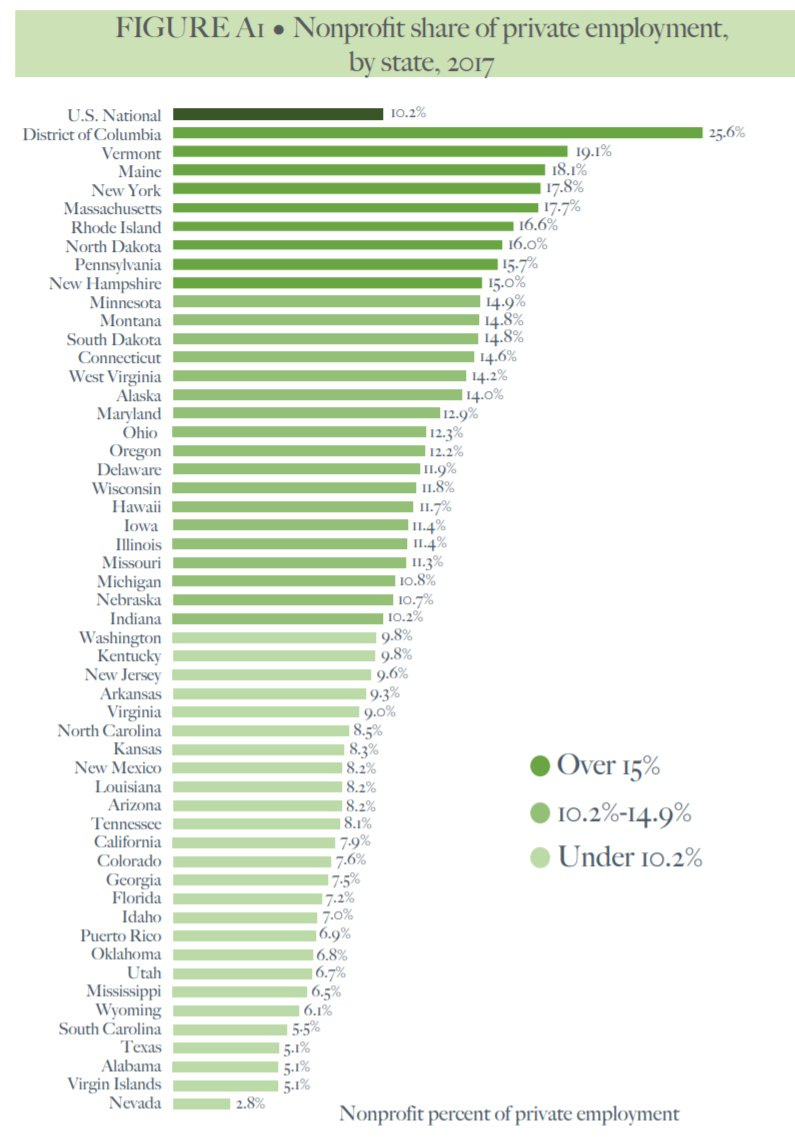

Ultimately, the size and scope of America’s nonprofit sector is powered by uncapped charitable deductions, an unusually progressive income tax, lax rules and oversight, the depth of US capital markets (creating windfalls that must be quickly dispersed to hit pay-out thresholds), and a large ecosystem of private foundations, trusts, and endowments. In 2016, 1.44% of US GDP was donated to nonprofit organizations, more than any other country and nearly twice as much as New Zealand, the runner up. Of the 45 largest private foundations in the world by endowment value, 27 are based in the US while Canada has only one. Simply put, the scale of private philanthropy in the US is unlike anything in world.

Separate from its ideological composition, the peculiar power of American philanthropy likely weakens US state capacity, creating intrinsic barriers to the left’s vision of social democracy. Sweden and Norway, for example, have some of the lowest rates of nonprofit employment in Europe, rivaled only by former communist countries. And yet they also have some of the highest rates of genuine civil society and social capital. The secret seems to be Scandinavia’s rich history of mutual aid, which culminated in universalistic, publicly administered social programs that crowd-out the need for third-party providers, combined with sector-wide collective bargaining agreements that crowd out the need for “advocacy without representation.” It’s a legacy that’s recently begun to reverse under what most lefty sociologists would recognize as the dreaded influence of neoliberalism, new public management theory in particular.

In this light, the conflation of “the neoliberal turn” with Reaganomics is about two decades too late. Instead, the regime change that displaced member-led parties and the countervailing power of robust labor unions first started, as Teles notes above, in the mid-1960s, when large foundations swelled on post-war growth and tax avoidance to fill the void. Collective bargaining and machine politics were summarily replaced with a technocratic “policy state.” And what’s a policy state without policy experts? Thus the modern advocate was born.

Needless to say, the results have been mixed. As Claire Dunning documented in her 2022 book, "Nonprofit Neighborhoods: An Urban History of Inequality and the American State," the new elect made it their project to solve America’s social problems — hunger, crime, urban poverty, racial exclusion and so on — through applied social science, administered via grants to a complex of nonprofit providers, evaluators, and technicians. A characteristic example was the New Careers for the Poor program designed to give jobs to those dislocated by urban deindustrialization:

In the 1960s, a new and popular theory of “new careers” proposed to address urban poverty and deindustrialization by growing the human services sector and hiring so-called nonprofessional workers to aid the delivery of those services. This strategy gained traction in social scientific, philanthropic, and bureaucratic circles and shaped Great Society legislation, which allocated federal grants to create entry-level jobs and professionalizing career ladders in the fields of health, education, and welfare. The implementation of this strategy had consequences for the human service organizations that received federal funds, as well as for the people hired into the new positions. Instead of building ladders to professional employment, efforts produced dead-end positions that left the predominantly African American women hired as aides in poverty. Even as the new careers experiment helped usher in a post-industrial economy, it reinforced the stratification of the labor market along lines of race, gender, and credentials.

Neoliberalism is associated with privatization. But delegating services to nonprofits is no less a form of privatization, particularly if they’re paid for by the tax-sheltered surplus value of long-dead capitalists. As Dunning argues, governments and foundations effectively “deputized nonprofits to help individuals in need, and in so doing avoided addressing the structural inequities that necessitated such action in the first place.”

Years ago, I sketched an analogy between think tanks and organized religion. After all, what are advocates but evangelists of a secularized social gospel dedicated to apostolic reform? Like Martin Luther, himself an Augustinian friar, the archetypal policy analyst contemplates — but then must share the fruits of his contemplation; to nail his Ninety-Five Theses to the legislature’s door (now in optional infographic form). America, being a country of Protestant nonconformists without an established church, has always had an unusually zealous religious economy, with schisms and denominations galore.

In a way, the devolution of US politics into a jungle of waring activists, each claiming to be building the one true “movement,” is a reflection of that same low church Protestant ethic. It’s enough to make me miss those old Anglican ladies and their triangular sandwiches.

fantastic piece

"Years ago, I sketched an analogy between think tanks and organized religion. After all, what are advocates but evangelists of a secularized social gospel dedicated to apostolic reform? " now do it for EA!

Bravo!