Libertarian Marxists or Marxist Libertarians?

Let's get critical

Marxists and libertarians have more in common than they care to admit.

Some trivial examples: Both ideologies favor radical reforms in the name of human emancipation. Both limit to anarchism or statelessness in favor of bottom-up self-organization. Both have been used to justify support for authoritarian regimes that imposed deformed versions of their ideals. And both attract young people for their moral clarity and analytical simplicity.

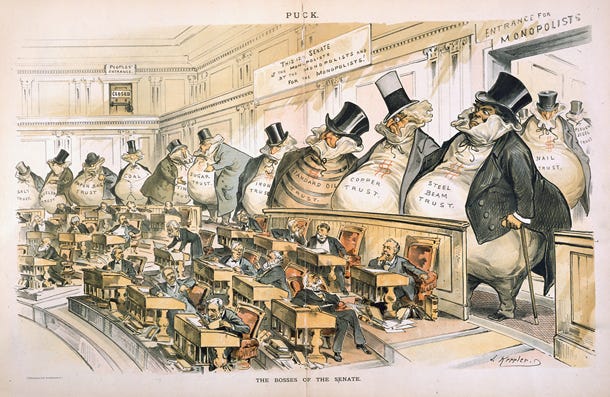

More interestingly, though, Marxists and libertarians both have sophisticated and surprisingly resonant theories of political capture — what each esoterically refers to as “political economy.” For the Marxist, our political institutions are captured by wealthy capitalists and their powerful class interests. The same is roughly true for the libertarian, only the crony capitalists aren’t always on the same team. Either way, both sides nod in recognition to the caricatures of politicians being paid-off by monocle men. They just disagree on which side of the transaction to shrink.

These similarities led economist Michael Munger to pose the question, “Was Karl Marx a Public-Choice Theorist?” Well, if you have to ask…

Munger argues that Marx anticipated several core ideas in modern Public Choice Theory, from the presence of “bootleggers and Baptists” dynamics, to the centrality of interest groups and rent seeking in the democratic process. As Marx and Engels wrote in the Communist Manifesto,

“The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing affairs of the whole bourgeoisie. … The ruling ideas of each age have never been the ideas of the government.”

Contrast this with the following claim from George Stigler, one of the Chicago School founders of Public Choice:

“As a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit. … We propose the general hypothesis: every industry or occupation that has enough political power to utilize the state will seek to control entry.”

Take the leftist and anti-capitalist historian, Gabriel Kolko. To his dying regret, Kolko found a proud fan in Murray Rothbard, who admired his scholarship for documenting an incestuous relationship between big business and Progressive reformers, from the New Deal through the Cold War. While the particulars of Kolko’s historical work don’t hold up, his screeds against “political capitalism” and “corporate liberalism” bare a family resemblance to the managerial corporatism forewarned by Joseph Schumpeter (an Austrian economist) and propounded on by James Burnham (an ex-Marxist). To this day, when one hears the term “professional managerial class” dropped in cocktail party conversation, one is never sure whether the speaker is on the socialist left or anti-statist right.

Hayek proposed his trickle-down theory of social change based on this purported influence of academics and public intellectuals. While Hayek was no Marxist, he implicitly accepted the idea that policy outcomes were downstream, not of the general will or noble statesman, but the prejudices of the bourgeoisie and their epistemic authorities. The “climate of opinion” among intellectuals exercises a “censorship function,” Hayek argued, putting certain ideas beyond the horizon of possibility. By seizing the means of intellectual production, classical liberals could thus put the bourgeois intellectual’s corporatist predilection in a box.

One such box was the impossibility of social calculation: whether or not socialism is desirable, Mises and Hayek argued that the challenge of aggregating local knowledge made it a technical impossibility. By the 1980s, Marxists realized they had a problem, so they started cribbing neoclassical methods. “Analytical Marxism” aimed to create a “non-bullshit Marxism,” in the words of G.A. Cohen, by supplying Marxist dialectics with rigorous microfoundations. This meant borrowing heavily from the methodologically individualist toolkit of Rational Choice Theory, of which Public Choice is just one application.

Rational Choice gave critical theorists a newfound degree of analytical traction after years of spinning their wheels. In particular, the theory provided a diagnostic tool for understanding the alienation and coordination problems induced by capitalism's narrow reliance on instrumental rationality. As Habermas argued, a comprehensive theory of social action must encompass both the means-ends coordination provided by external systems of incentives, and the communicative coordination provided by language, norms, and interpersonal deliberation. Markets and modern bureaucracies tend to displace the latter with the former, dismantling traditional modes of life — “colonizing the lifeworld” — in favor of explicit procedures, price signals, and social sanctions. The Chamber of Commerce and neoliberal Democrats’ joint effort to crowd-out faith- and family-based child care with specialized “Early Childhood Educators” comes to mind.

A nation of rebels

Unfortunately, the legacy of the Analytical Marxists (by far the best kind!) was overshadowed by their trendier, New Left comrades. The New Left made distrust in government instinctual and thus rejected Fabian reformism in favor of direct action, quixotic community building, and self-expressive individualism. Equally unfortunately, these same trends were mirrored on the countercultural right. Indeed, once you learn that Timothy Leary gave a speech at the 1977 Libertarian Party convention predicting the internet would one day overthrow the government, American politics in 2022 makes a lot more sense.

Marxists and libertarians thus subdivide based on whether they privilege their System 1 or System 2 mode of reasoning. The libertarianism of Hayek et. al., while clearly not rationalistic, is still decidedly rational, in that it roots itself in a cognitively taxing argument for the superiority of the rule of law and spontaneous order. The libertarianism of Rothbard and Leary, in contrast, is rooted in reflexive non-conformism and a guttural contempt for authority. Likewise, Marxism has both its careful historiographers, a la Eric Hobsbawms, and its radical subjectivists, a la Herbert Marcuse. Choose wisely!

In both camps, the romanticists seem to dominate the current moment. The left is enthralled by standpoint epistemology and inchoate demands for racial justice that dispel with any discursive responsibility to connect means to ends. The right, meanwhile, acts like it’s one dank meme and Publius Fellowship away from the vanguard party needed to overthrow the woke capitalists and restore the Republic. Only then will we hunt in the morning, lift in the afternoon, pray in the evening, and own the libs after dinner.

One of my first trips to the US as an adult was for a Liberty Fund-style seminar nearly a decade ago, when the Tea Party wave was still fresh. Such seminars normally involve a libertarian academic leading students in a discussion of Adam Smith or whatever before heading to an open bar. This time we were assigned excerpts from Alinsky’s Rules For Radicals. Strange. Was the goal to know thy enemy, or become them?

Personally, I prefer my politics without romance and my individualism without metaphysics. But maybe that’s just the false consciousness talking.