Empiricists vs. Extrapolators

A core divide in how people think about AI

Shortly after the launch of ChatGPT in 2022, I wrote an essay called Before the Flood: Ruminations on the future of AI. It seemed obvious to me that ChatGPT was an early indicator of a fast-approaching tsunami, although at the time not everyone agreed. It can be hard to remember now, but dismissiveness about language models was more the norm than the exception. It was as if the ocean had suddenly receded eerily far from the shoreline while most beachgoers carried on like nothing had changed.

Today, fewer people need convincing that AI is a big deal. If you squint, you can even see the crest of the wave on the horizon. And yet opinion still varies widely on the exact size and timing of AI’s impact. While the beachgoers have largely left the beach, many “tsunami optimists” are still stubbornly ignoring the official forecasts, believing they can ride out the wave from their high-rise and that only gullible “doomers” run for the hills.

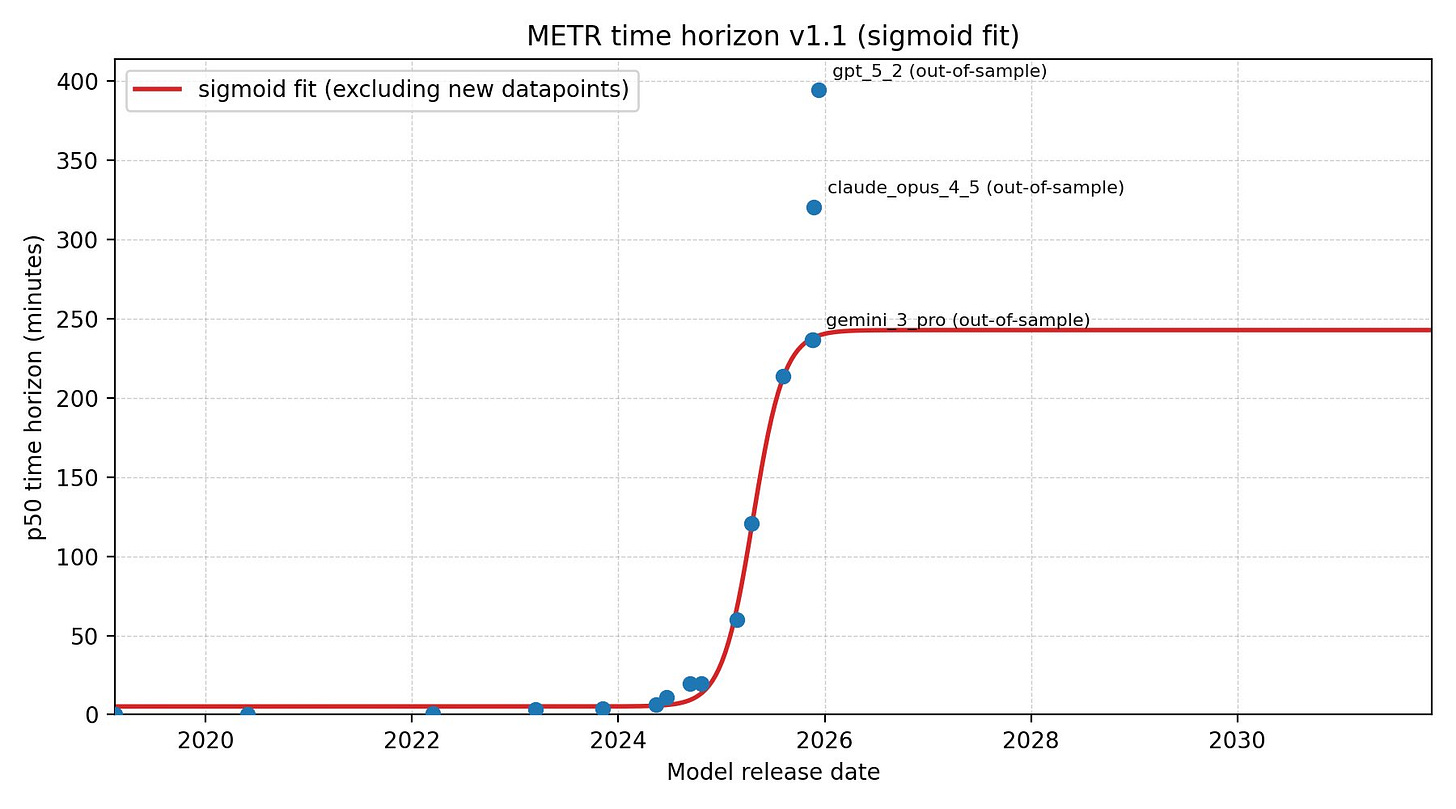

The phenomenon of people repeatedly underestimating the pace of AI progress is an example of exponential blindness. An amusing case of this was seen with the recent release of a preprint from UPenn researchers that attempted to cast doubt on METR’s forecast of AI’s accuracy on long-horizon tasks (our current best measure of AI autonomy). While a simple extrapolation suggests the task-length that an AI can reliably perform is doubling every 5-7 months, the UPenn researchers argued that the apparent exponential is actually an S-curve on the verge of plateauing. That same day, OpenAI and Anthropic both released new models that showed the exponential trend was alive and well, effectively debunking the paper in real time.

I’ve thus taken to dividing the AI commentariat into empiricists and extrapolators. The empiricists often claim the epistemic high ground, preferring hard data over so-called “towers of assumptions.” In practice, however, this often reduces to a version of “I’ll believe it when I see it.” Don’t get me wrong: empirical data it essential to forming a coherent model of the world. At the same time, pure empiricism has a tendency to collapse into a kind of Humean skepticism, as though our repeated observations of the sun rising in the east give no guarantee that it will again tomorrow.

Extrapolators, meanwhile, are often dismissed as a-theoretical, “line go up” curve fitters, and while those types certainly exist, there is a word of difference between the people who do “technical stock analysis” by drawing lines on price charts and the people who construct deep structural models to make rigorous, out-of-distribution bets. On the contrary, it is usually the empiricists who are a-theoretical to a fault, leading them to overfit sparse data with epicycles upon epicycles rather than commit to a formal model that attempts to generalize the underlying process.

Extrapolators have a remarkable track record in the AI field, being repeatedly early to trends and capabilities that empiricists believed were still decades away. They did not simply get lucky by drawing straight lines on a graph. Rather, they grounded their extrapolations in a first-principles understanding of physics, biology, neuroscience, statistical mechanics and other relevant fields. The founding team at Anthropic, for instance, built their strategy around a high-conviction bet on scaling laws being more than just an empirical regularity, but rather something genuinely law-like. The success is a testament to the power of simple priors and heuristics, such as Ilya Sutskever’s famous quip that “models just want to learn,” or Ray Kurzweil’s 1999 forecast of human-level AI by 2029 based on little more than an extrapolation of Moore’s Law.

The extrapolators’ conviction in scaling laws is part empirical, part theoretical. On the empirical side, AI researchers have by now measured the predictive accuracy of scaling laws across many orders of magnitude. On the theoretical side, there is good reason to believe these scaling properties generalize across diverse modalities. In essence, once a training method starts to work a little bit — once a “hill” starts to be “climbed” — it is safe to assume that we’ll reach the summit sooner rather than later. Once video generation models started to work at little bit, for example, it was only a matter of time before it would be possible to generate life-like movie sequences. In other words, that we would soon have video models as good as the new Seedance model from Bytedance was in a sense knowable from at least the first, heavily distorted video of Will Smith eating spaghetti — if not from the days of Alexnet.

Empiricists often retort that predicting the future is impossible because the world is a complex system, but this is only half true. The world may be complex, but complex systems are typically controlled by a small number of highly stable invariants. Moreover, the complexity of a systems is often scale-dependent, becoming stable in regimes where chaotic dynamics average out. This is why it is easier to predict the earth’s average temperature a century from now than to forecast the weather in three weeks. The former is controlled by basic thermodynamics and a handful of parameters, while the latter is highly sensitive to initial conditions and small perturbations a la the butterfly effect.

Forecasting AI capabilities is closer in kind to solving a thermodynamics equation than solving the three-body problem. This doesn’t mean it’s easy; only that it is possible. It is also necessary, as human institutions move vastly slower than the pace of AI progress. Preparing for AI thus means preparing for capabilities that do not yet exist, but which we can have some confidence will exist by the time our preparations are in place.